Scotland Fulbright Endings

June 28th, 2021Audio field recording is an activity that involves taking equipment out into environments, whether natural or urban, to capture sound. It is an activity that can capture the rare vocalizations of individual species, like oystercatchers and lapwings. It can also capture the sound of a place, or its soundscape. These soundscapes can be an important tool for understanding the unique elements of a location and how the local environment evolves over time, a practice that is often called acoustic ecology. Acoustic ecology is an interdisciplinary topic that draws on music, acoustics, geography, environmental studies, and so many others, which makes it a great vehicle for engaging different parts of the university in conversation.

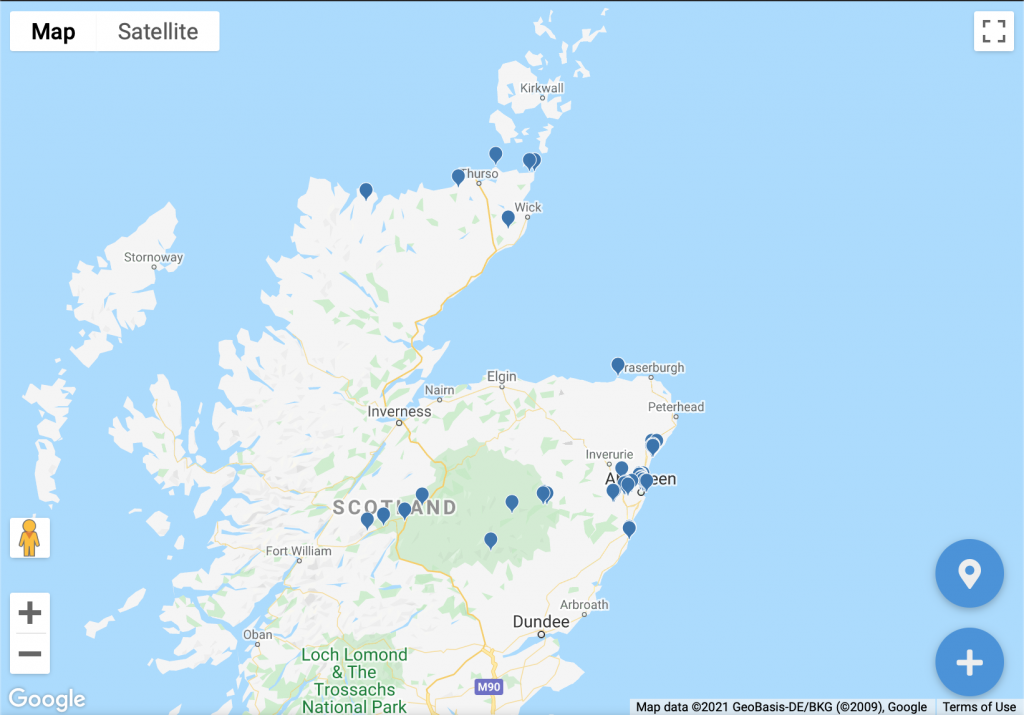

After six months spent recording in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, I have a much better understanding of why its coastal soundscapes so special. Thanks to my Fulbright, I was able to visit dozens of sites managed by a variety of organizations (NatureScot, Scottish Forestry, National Trust, RSPB, and others) around northeast Scotland and captured over 34 hours of audio. I also captured the soundscape of many places with very few visitors (and sometimes none), because I was often ready to visit as soon as they opened from any lockdown restrictions. I will be leaving Scotland with over 90 gigabytes of audio recordings, and also agreed to leave a copy of this data with my counterparts on the faculty at the University of Aberdeen.

My primary collaborator on the Aberdeen faculty has been Dr. Suk-Jun Kim, who I have actually known for about 20 years. He spent four years living in Gainesville to do his doctoral work at the University of Florida, about 2 hours drive from where I teach at Stetson University. I was born and raised in Florida and spent most of my working years there, so I am very familiar with the state and its coastal soundscapes. Now that I have spent six months living in Aberdeen, we have this unique connection as professors in the same discipline familiar with both Florida and Scotland. It would be a shame not to continue to collaborate and capitalize on that connection.

Dr. Kim and I have discussed a framework for continuing the collaboration between Stetson and Aberdeen, and we both agree that getting our students involved is essential. Neither campus currently has a course in acoustic ecology, so we have a blank slate. When I first wrote my Fulbright proposal, I had dreamed that it might be possible to eventually use my research and experience in Scotland to design a travel course. It would be something that would allow me to first study a topic with Stetson students on campus and then lead them on a short-term visit to Aberdeen that puts theory into practice. Prior to the pandemic, these were popular offerings at my institution and really helped get students thinking globally about significant challenges, like our collective environmental responsibilities. Since the pandemic, the immediate future for these types of learning experiences is unclear. Things like quarantines and COVID testing add to the already complicated logistics. So we’re hesitant to begin planning something like this until the restrictions on travel become more relaxed.

Because it will be a difficult climate for travel courses in the immediate future, we brainstormed a bit and thought we could instead leverage online learning to connect our campuses. Both institutions are more comfortable with these technologies since the pandemic essentially forced their mass adoption, so why not leverage these tools to foster international exchange? Our idea is to embed online meetings between our students into new courses that we each teach for our respective campuses. Students in Aberdeen and Florida could discuss readings and issues that explore the topic of acoustic ecology together. They could also return to specific sites that I recorded this past year and report on how the soundscape may have changed, which would help form the basis for long-term monitoring of how both places are evolving. We also want both courses to be open to students from any discipline, which would enhance the diversity of perspectives on this issue. It’s going to be a challenge, but if it works, it will mean this Fulbright experience has set the foundation for some exciting long-term, interdisciplinary collaboration in acoustic ecology.

Because the creative outcome from Canaveral ended up being significantly larger than I originally planned, I felt justified focussing my time in Scotland more on collection of material and field work. As I was fond telling people, “the one thing I can’t do back in Florida is record Scotland.” It was certainly an adventure collecting the sound of species like guillemots and gannets that I would never encounter back home. My plan is to head back to Florida with my treasure trove of Scotland recordings and figure out something creative to do with them when time permits. Even though I am happy with what I personally achieved in Scotland, I left with a palpable desire to return to Scotland when circumstances are more normal to explore the soundscape again and enjoy a few more face-to-face conversations with the wonderful people I met along the way.

Leave a Reply